Scantron machines and old treadmills: How colleges handle unwanted tech

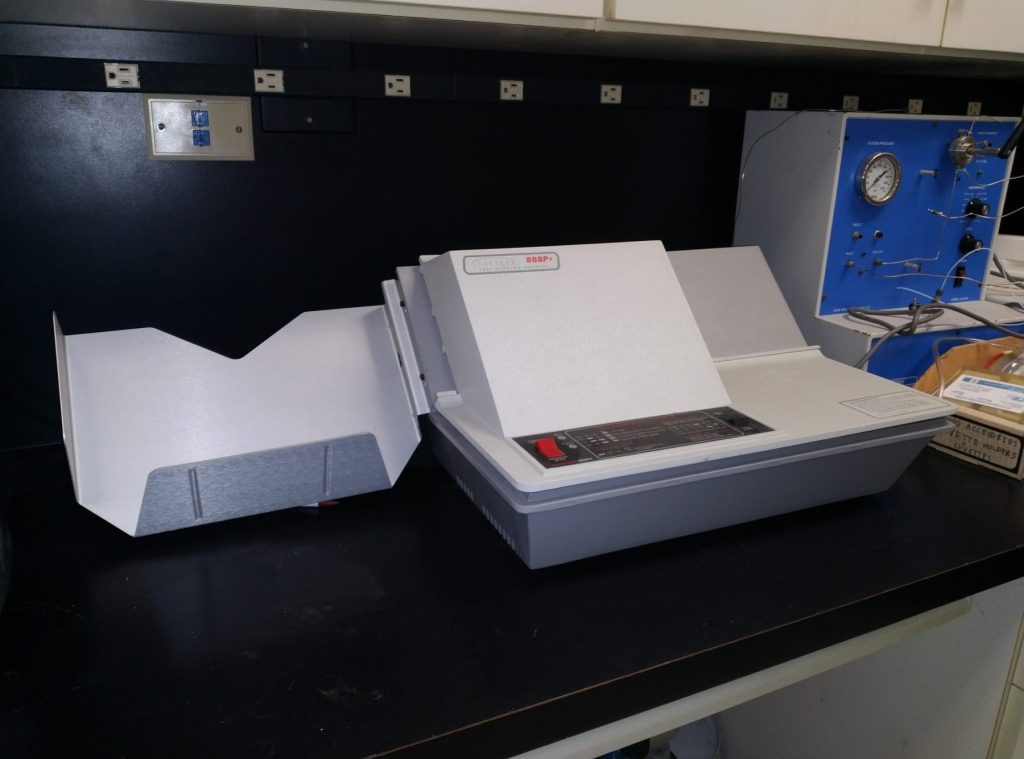

The science labs at La Sierra University, a private liberal arts college in Riverside, California, are full of antiques.

They’re not the kind of treasures that you’d find in a museum or fancy store, but they are artifacts of a bygone era — an era of floppy disks, the Windows XP operating system and test-scoring machines built by the Scantron Corporation.

Scantron machines, despite being clunky and finicky, have demonstrated incredible staying power in education, and students taking multiple-choice tests today are still well-acquainted with the green bubble sheets of yore. But slowly, that is changing, said Jennifer Helbley, a chemistry professor at La Sierra, who has taken a leading role in tech procurement, maintenance and management.

Helbley and her colleagues have over the years explored options for grading multiple-choice tests at scale, each coming with its own quirks and challenges. Recently, the department transitioned to a digital product called Gradescope, a relatively new offering from a company called Turnitin.

“One of the things that frustrated me the most about using Scantrons was that it was incredibly easy to screw up and incredibly difficult to fix an error once you found one,” said Helbley.

With Gradescope’s online interface, it’s easy to create and change answer keys, alter student responses and grades, examine trends and export analytics, Helbley said. Best of all, there’s no proprietary scanning equipment needed — any scanner will work.

So why is there a Scantron still sitting in La Sierra’s chemistry department?

A technology safety net

Many academic departments, particularly in the sciences, hold on to old tech, including Scantrons, out of an abundance of caution, explained Helbley.

“We’re not always sure if the new technology is going to stick around, whether it’s going to be affordable, and if it is going to do everything that we need,” she said.

Some people are also slower to adapt to change than others.

“There’s always at least one person who says they’re going to keep using this old way of doing things because that’s how they’ve always done it and it’s worked for them,” Helbley said.

Competing priorities, especially during the pandemic, also make it easy to delay decisions on what to do with old tech, particularly if there isn’t a consensus or it isn’t clear what the disposal options are, she said.

Small liberal arts colleges and major research institutions struggle with what to do with aging technology. IT modernization, particularly the shift from on-premises data storage to cloud-based solutions, is happening more and more in higher ed. And while there are conversations about sustainability, in terms of how long technology solutions will last, there seem to be fewer discussions about the environmental impact of mountains of equipment going to landfill.

Minimizing waste, maximizing reuse

There are, fortunately, alternatives to throwing unneeded tech in the trash, says Tim Heckaman, information technology administrator at Michigan State University’s Surplus Store and Recycling Center.

Most institutions will have some kind of system for managing surplus equipment, said Heckaman, but often surplus operations are part of asset management, and only deal with assets over a certain value. At MSU, surplus management and recycling are combined under a unit that also encompasses groundskeeping, building maintenance and general refuse — a structure that has helped the institution process more of its waste in environmentally friendly ways.

Student activism led to the creation of MSU’s recycling center back in the 80s. Today the center is responsible for processing 20 to 25 million pounds of material left on campus annually.

“Our primary goal is to reuse something over recycling it or putting it into e-waste,” said Heckaman.

He handles anything discarded on campus that’s electrical or can be plugged into a wall, including lab equipment, computers, printers, gym equipment or vehicles. If he or his colleagues can’t find an immediate use for an item on campus, they attempt to sell it in the MSU Surplus Store or an auction website.

Heckaman and his colleagues attempt to fix the items they receive even if the resale value is low, but it’s sometimes a difficult judgment call. There isn’t a lot of interest in old Pentium computers, for example, and the team “has to weigh how much time we invest versus its value.”

Facebook on a treadmill

Before electrical items can be resold, any data on them has to be wiped. There’s a surprising amount of personal data stored in equipment that you wouldn’t always expect, said Heckaman.

“I had a treadmill come through a couple of weeks ago that had somebody’s Facebook account on it,” he said.

Wiping the Facebook account involved contacting the treadmill manufacturer for a special code, which the company sent by mail on a USB drive.

“We can’t do that on everything,” Heckaman said.

Often with items, such as lab equipment, there’s a lot of research involved in figuring out what the device is, whether it has some kind of storage media and whether it can be wiped.

“I’d love to be able to work with manufacturers on having a better way to wipe data for resale, but that’s on the manufacturers, and some won’t even allow it,” he said.

Photocopiers, scanners and printers are a particular headache for Heckaman, as often information is stored on a device’s inaccessible hard drive.

“I’ve contacted Xerox, Canon, Kyocera, all these major brands, and they’ve all told me the same thing — If you want to get access to our software, you need to become a contractor with us, take a class, and work for us,” he said.

If the storage media can’t be wiped, the university disposes of the device. MSU has a contract with an electronic-waste company, which charges for disposal by weight, something that can quickly add up.

Even at MSU, an institution with a large infrastructure for reselling, recycling, and reusing tech, not everyone on campus is aware of those services, Heckaman said. He said the university could also further encourage the reuse of items the campus already owns, not only to reduce waste but save money. Many departments, for example, are overly wary of purchasing second-hand computers, he said.

“I’ve tried to talk to some departments to offer a kind of pseudo-warranty where we’d keep a certain amount of computers and stock that are those models, and I could have these parts ready for them when needed,” said Heckaman. “A lot of people think they need new computers.”