Purdue U.’s ‘BattleFlow’ brings data to military classrooms

To help students in military classrooms understand the battlefields of the past, present and future, a team of researchers at Purdue University is developing a simulation tool that relies on virtual reality and ideas borrowed from fluid mechanics.

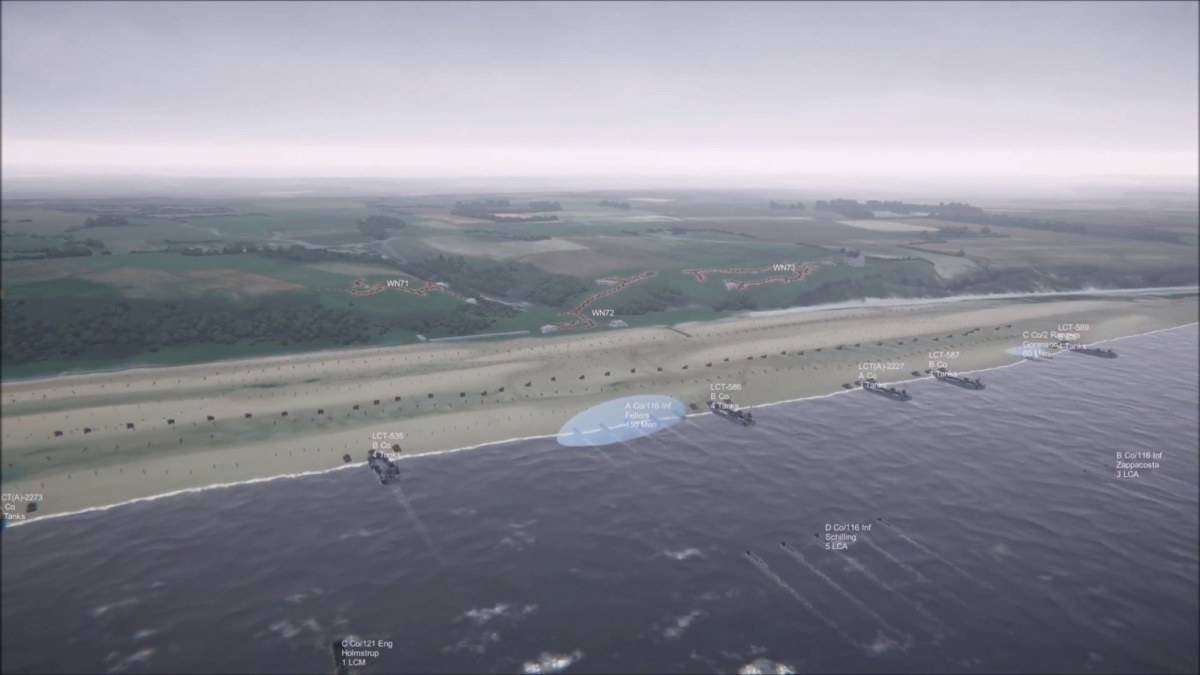

The software, called BattleFlow, renders simulations of battlefields with user-defined conditions that can be viewed through virtual reality headsets or on desktop displays. Sorin Adam Matei, a Purdue communications professor who’s leading the project, said that although the software includes a VR frontend, it’s not intended to be a video game, nor to recreate battlefields in a visually realistic way.

“It’s meant to be an educational tool,” Matei told EdScoop. “It’s [accurate] enough to help people judge their decisions and make better decisions, which is our ultimate goal, to help military officers and people in the know formulate decisions that take into account reality and facts, not just gut feelings.”

The software, which is slated for commercial release in mid-2021, he said, can be thought of as a “decision support system” or a “homework engine for military officers.” Though designed as a generic tool that can be applied to battlefield scenarios of any era, Matei and his team of graduate students and military officers began by applying the engine to the Omaha Beach landing in Normandy during World War II, which has been dramatized in films like Saving Private Ryan.

Using BattleFlow, a user can establish starting conditions for the battle, such as where to position units, and how many, and then run the simulation. A probabilistic model generates the expected movements of troops based on “military force,” a concept that accounts for physical power of people and their technology.

“As long as you model your force as a fluid, it can be anything. It could be missiles, it could be arrows, it could be tanks, it could be hypersonic missiles,” he said. “In this respect, our model can take any type of human military organization with any type of technology to predict its movement. It could be ancient, it could be modern, it could be future.”

Matei imagined that the tool could be used for homework assignments in which military students are given certain benchmarks, such as moving their troops to an objective while suffering only 25% casualties, for example.

The analytic engine is intentionally limited, he said, by excluding the variables of morale and command, but those elements may play a greater role in how the software generates its outcomes in future versions after the group conducts further research into those topics.

As the flagship project of the FORCES, or Strategy, Security and Social Systems Initiative, at Purdue’s College of Liberal Arts, Matei said the project benefits from the expertise of a diverse group of students whose backgrounds range from traditional graduate students to military officers seeking doctorates.

He said the project also benefits tremendously from some of the university’s existing infrastructure, such as Purdue’s Envision Center, which provides advice on development of the software’s VR component.

As the use of data becomes more enmeshed into how people and organizations of all types make decisions, Matei said he hopes this project will introduce more of a data-driven approach into military strategy and education. He compared the introduction of analytic tools like BattleFlow to that of diagnostic tools — such as imaging machines and blood tests — to medicine, which freed physicians from the necessity of relying only on limited empirical observations and their often-faulty intuitions about that information.

“I’m extrapolating a little bit,” Matei admitted. “This is just a little training tool. I cannot say that we solved the problem, but we’re going in that direction. The world is going in that direction and we’re trying to follow it.”