Are schools getting justifiable value out of their student surveillance?

As schools increasingly prioritize the physical security of their campuses and proactively identify at-risk students online, administrators have increasingly used emerging technologies like facial recognition and police-integrated social media databases. But if K-12 schools are trying to ensure the safety their students, said American Civil Liberties Union senior counsel Chad Marlow, then they must also examine whether these surveillance technologies are also impeding First Amendment rights.

“There’s the assumption baked in that surveillance of students is helpful,” Marlow told EdScoop. “Let’s not assume reflexively that tech is going to provide us with the answers to this problem.”

The potential harms, he said, arise from monitoring student behavior online and outside of the classroom to the point where school systems blur the line between law enforcement and educator.

A 2018 Florida mandate collects the social media information of students and combines it with law enforcement data into a centralized database. Georgia lawmakers are floating a bill that would create “student profiles” using records from schools, local and federal law enforcement and state social service agencies. The Federal School Safety Report, released in December, advocates for schools to monitor the social media of students. The implication of these initiatives, Marlow says, violates primary American principles.

“When schools surveil students … it impedes their freedom of speech and communication. Students won’t speak and communicate freely on platforms when they know they’re being watched,” he said.

Marlow explained that using technology to monitor student behavior inside or outside of the classroom could infringe on the ability of students to conduct research on fringe academic topics or political stances, or label them as threats without justification. He added that any schools using facial recognition to secure their buildings might target minority students, since some instantiations of the technology have been shown to be less accurate when scanning minority students.

Marlow says the question shouldn’t be which technology works best to surveil students, but if administrators should be doing it at all.

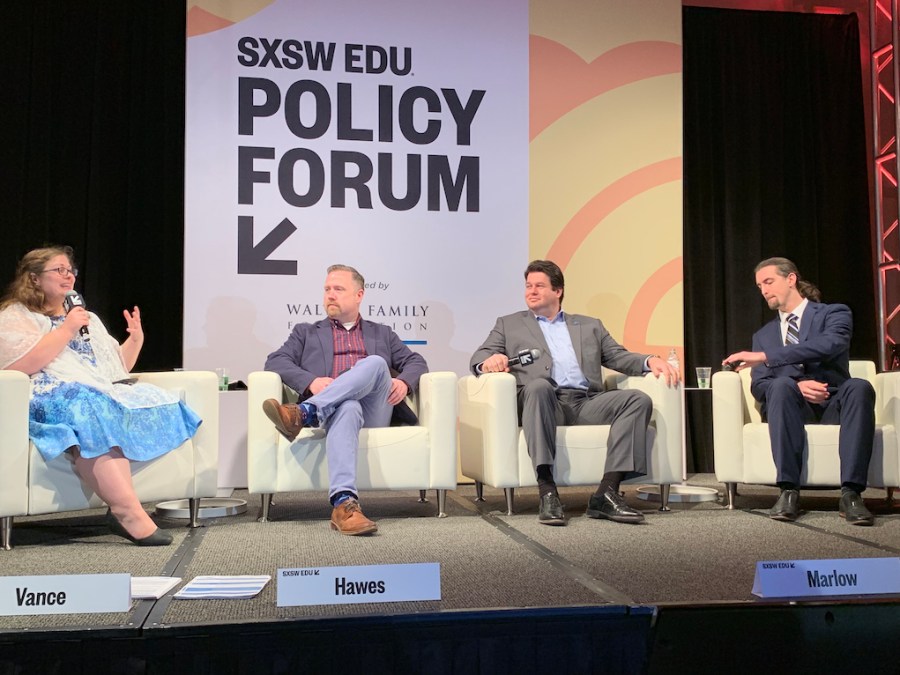

“It is the desire to come up with a quick, demonstrative technological response to a societal problem,” said Marlow, speaking onstage at a South by Southwest EDU panel examining the link between student privacy and safety earlier this month. “Not saying whether it’s good, bad or indifferent — but you need to investigate whether [data collection] is actually valuable.”

Michael Hawes, the director of privacy policy for the Department of Education, said that Americans accept a certain degree of surveillance all the time via ubiquitous cameras or data collection on their mobile mobile devices. He pointed out that most of the time, people glean some value or service from this paradigm and that student data needs to be held to the same standard.

“We make those decisions by asking ourselves whether the value we’re getting back is worth the intrusion into our lives,” Hawes said. “The concern I see in the emerging technology and emerging approaches to surveillance is that we’re talking about collecting a lot more data on students, but we’re not having that discussion about the value we’re getting back and the risks to that collection of information.”

There are non-technological tools that can help schools be proactive about safety, Marlow said, such as increased mental health services for students, anti-bullying initiatives and a focus on social-emotional learning programs.

Denver Public Schools’ student data privacy officer, Bryan Westerman, said that a given tool often doesn’t matter as much as the environment it’s placed in. The key, he said, is engagement with the community, because not every district will arrive at the same solution.

“Listen to families,” Westerman said, “and ask ‘what are you concerned about?'”